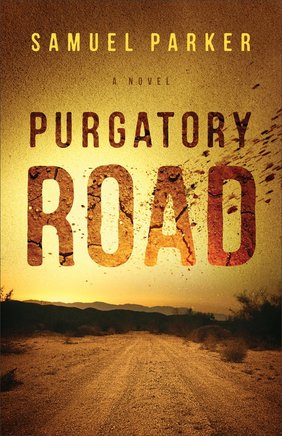

Written by Samuel Parker When a day trip out of Las Vegas with his wife takes a turn for the worse, Jack is sure that he has the ability to get them home. But he drove into something far beyond reason. Rescue comes in the form of a desert hermit, but hope fades as the couple realizes that the nomad has no intention of letting them leave. A chance encounter with a kidnapped runaway and her crazed abductor leads them all farther into the wilderness—and closer to the cold brutality that isolation brings. At the edge of his sanity, Jack begins to learn that playing by another’s rules may be the only way to survive. In a voice that is as hypnotizing as a desert mirage, debut novelist Samuel Parker entices readers down a dangerous road, where the forces of good and evil are as crushing as the Mojave heat. This is suspense in its purest, most unfiltered form.  Fragments of Imagination There is a scene from the film adaptation of A River Runs Through It where the young Norman Maclean presents his father, his schoolmaster, with a piece of writing. Norman hands in his composition and his father marks it up with red, telling him “Again . . . half as long.” This happens several times until the writing is approved, thrown in the trash, and the boy runs off to fish. The Art of Brevity In a world where the mark of a “true” writer seems to be the word count tally of the day or week or month, brevity can be a sign of lack of discipline. However, brevity can be a valuable tool to wield and provide space for a reader to incorporate their own imagination into your story. One of my favorite chapters in my book Purgatory Road has only 48 words. It looks a bit odd in book form, taking up less than a half page. But I feel it is one of the more unique chapters in the book, as it conveys so much more emotion, context, and suspense than what would have been accomplished at 10 times the word count. (For context, the couple is stranded in the Mojave for a long while when we arrive at this scene.) 17 Morning light skirted the eastern ring of the valley as gently as an Easter sunrise. “Jack,” she whispered. “Yeah?” “Jack . . . water?” “No.” “It’s all gone?” “Yeah,” he said. “Oh.” “Sorry.” “Okay.” They drifted in a daze between waking and oblivion. “Jack?” “Yeah?” “I thought you left.” “Nope.” “Okay.” Brevity causes you to be confident in the words you have chosen, and confident that the reader will add what is flexible and implied, giving them more investment and bringing the story to life with much more vividness as it becomes laced with their own imagination and memory. One perfectly placed sentence can cut to the heart of a thought as quick as a Ginsu and with just as much ferocity. In fact, I think it can do more to impress on the reader the gravity of the story than burying them in superfluous prose. The Sound of Silence Music composition uses silence just as much as sounds. A pause or muted part allows the listener’s mind to wander, reflect, or ponder, as one writer said, “what it is that echoes in the silence.” [1] I would argue that sentence, paragraph, page, and chapter composition can accomplish much of the same effect. The problem that surfaces is our fear of trusting the reader to imagine our world in their own minds, to relinquish the keys of creation, and let a fragment echo in the silence and expand apart from the written word. In Purgatory Road, I use fragments to a level that caused my editor a bit of concern. Sentences are not supposed to look like this; even Microsoft tries to flag our attention and scream “This is wrong!” Below is an example of something I like to do in controlling the pace of a narrative with single words: Laura stared out of the windshield. The road ran off out of sight, disappearing into the horizon, mesmerizing in its seemingly magical disappearance. Alone. She thumbed her wedding ring in absentminded play, the sweat beginning to seep out of her skin, causing the band to roll freely around her finger. She looked at it, its jewel sparkling, shining in the rays streaming through the glass. The “Alone” gets grammatically flagged, but as read, it causes the reader to stop. A bullet. Even if it’s only for a fraction of a second, the reader has to contemplate that word in isolation. It’s more forceful than saying “she was all alone sitting in the car.” Alone. There is something slightly menacing in reducing the clutter and getting down to the raw bone of what you are trying to say. The world is not binary, so this bit of advice will not work for all occasions. Some things need explaining, some do not. But I would challenge you to look at your recent work, the one with the mega word count that you celebrated to your friends on Twitter about, and hear the voice of Norman Maclean’s father as you reread it: “Again . . . half as long.” You may surprise yourself by how a more direct and simple word choice cuts down to the marrow of the story you are trying to tell. [1] http://www.slate.com/articles/arts/music_box/2009/08/silence_is_golden.html.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Follow meArchives

May 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed