|

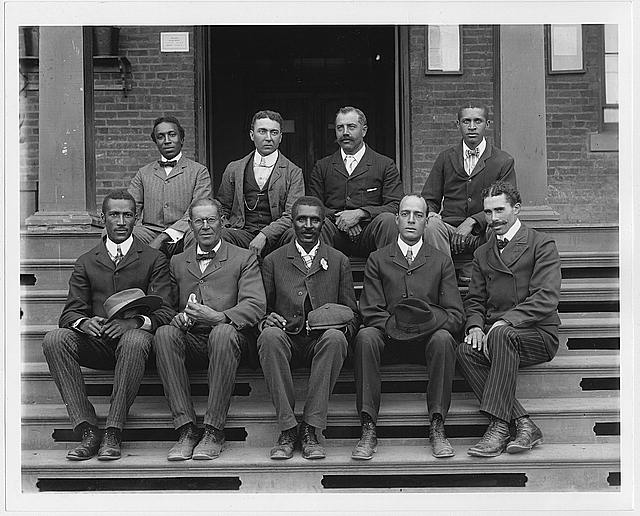

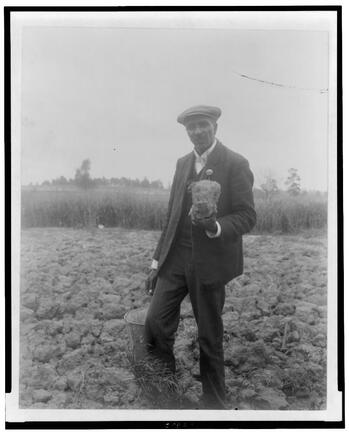

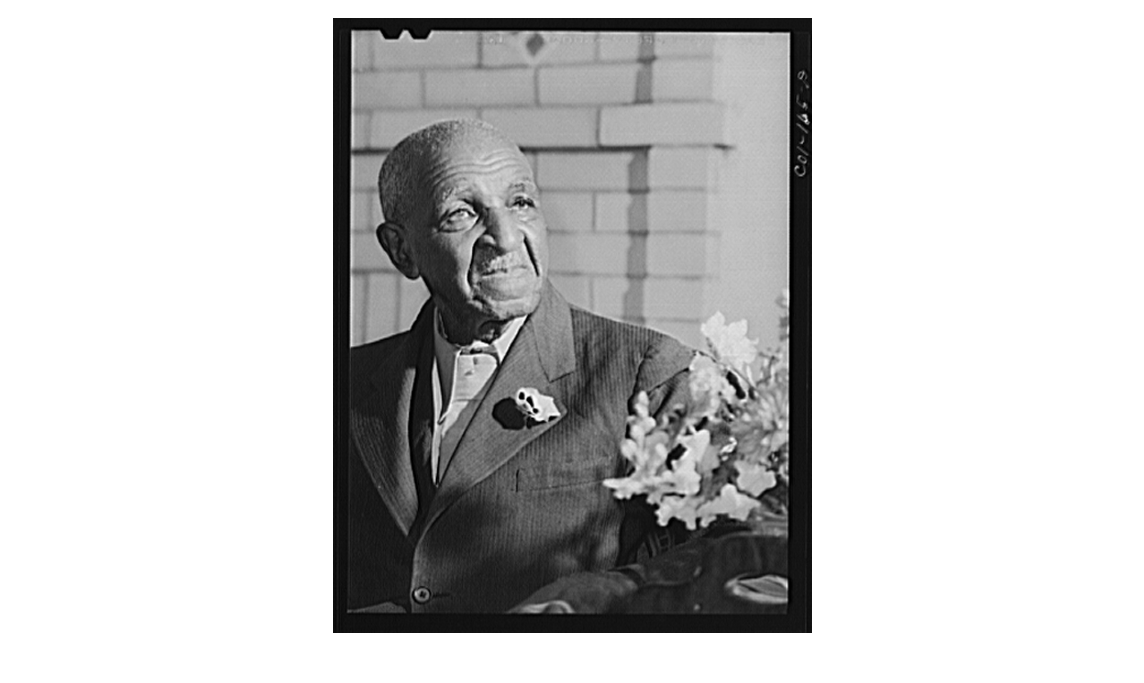

Welcome back! Last week we began the story of George Washington Carver and paused just after he received the Master’s Degree he had worked so long to earn. The same year that George earned his degree, Booker T. Washington invited George to move to Alabama to join the faculty of Tuskegee Institute as director of the school’s new agriculture department. Booker, an important African American leader, wanted Tuskegee Institute to teach African Americans practical skills to better themselves as well as achieve better-paying work and eventually, through patience and cooperation, raise their people above the social and political injustices they were currently facing. George, having seen the effectiveness of that approach in his own life, agreed with Booker’s goals and likewise agreed on April 12, 1896, to take the job Booker offered him. George wrote to Booker, “[I]t has always been the one great ideal of my life to be of the greatest good to the greatest number of 'my people' possible and to this end I have been preparing myself these many years; feeling as I do that this line of education is the key to unlock the golden door of freedom to our people.” George’s desire to help others stemmed from his childhood faith. As a boy, George had visited a church near the Carver farm. Then when George lived with the Watkins, Mariah passed her faith on to George along with her knowledge of herbs. George’s year at the Methodist Simpson College continued to develop his faith. Their acceptance of him regardless of his skin color had a marvelous influence. Years after his time there, he recalled, “They made me believe I was a real human being." George’s faith provided another motivation for his transfer to Iowa State Agricultural School; he wanted to develop the scientific abilities God had given him in order to help his people in the best way he could. After attending Iowa State, he spent the rest of his life serving at Tuskegee Institute. George’s service to students extended far beyond lecturing in his classroom. His ecstatic, exuberant, and entertaining lectures on the magnificence and usefulness of the natural world did indeed cause Booker to observe, “There are few people anywhere who have greater ability to inspire and instruct as a teacher…." But George didn’t just teach about science. On Sunday nights for thirty years he led a Bible class. He also spoke at organizations trying to bring unity to a nation divided by the color of people’s skin. As George’s popularity spread through Tuskegee and beyond, young men, both black and white, came to him to learn how to deal with the difficulties and divisiveness of the world. George sympathized with their problems and pointed them toward faith in a good Creator and ultimate justice. He mentored them, knowing that these young men would shape the future of America. To one of his beloved boys, George wrote: "Not a day passes that I do not think of my boys and often wonder just what they are doing…. It is such an inspiration to me to watch the progress that you and your brother have, and are yet, making, and the future that will doubtless be yours as young aspiring American citizens who must figure into the building up of this great American commonwealth…." George served many people through his scientific research, too. George saw farmers struggling harder and harder to make their fields grow enough cotton to sell to support themselves. Trying to understand the problem, George used chemistry to examine the dirt. He realized that growing so much cotton for so long in the same fields had used up the nutrients in the dirt. George’s next step was to find an inexpensive, easy solution to the problem that poor farmers without many resources could use. George experimented with rotating crops and demonstrated that temporarily growing peanuts or sweet potatoes instead of cotton would refresh the soil’s nitrogen content and create a better cotton crop the next time cotton was planted in that field. This was a marvelous first step toward a solution, but farmers next needed to be able to use and sell all the peanuts and sweet potatoes they grew. So George went back to experimenting. Tuskegee records that George worked on over 100 different ways to use sweet potatoes (click here for a partial list) and 300 different ways to use peanuts for food, medicine, cosmetics, dyes, and many other needs (some listed here). George also knew he needed to figure out ways to share his research with the farmers and to convince them to try his ideas since not everyone could or would travel to see his work in person. So George took Booker’s idea of a “traveling agricultural school” and invented the Jessup wagon to bring demonstrations of his research directly to farmers in their own fields and communities, letting farmers see the stupendous results for themselves. George spread his research through writing, too; despite a lack of funds and help, George published forty-four bulletins (a sort of information pamphlet) with titles like, “How to Grow the Peanut & 105 Ways of Preparing it for Human Consumption,” and “Possibilities of the Sweet Potato in Macon Co.” (Tuskegee maintains a full list of George’s bulletins here.) Read "The canning and preserving of fruits and vegtables in the home" by George Washington Cover @ the button below.George’s work succeeded and his fame grew. In 1921, George’s presentation on the usefulness of peanuts before the U.S. House of Representatives’ Ways and Means Committee won government protection for the peanut industry and the title “The Peanut Man” for himself. His first college, Simpson College, awarded him an honorary Doctor of Science degree in 1928. At the beginning of George’s career at Tuskegee, virtually no one was growing and selling peanuts. Fifty years later, peanuts were in the United State’s top six major crops. By 1940, the growing and selling of peanuts were second only to cotton in the South. George’s influence reached U.S. national figures like Henry Ford and Presidents Calvin Coolidge and Franklin Roosevelt and extended beyond the Atlantic Ocean; leaders of other nations asked for his advice to help their people. He was even selected to join Britain’s Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures, and Commerce. After George passed away on January 5, 1943, President Franklin Roosevelt established a monument in George’s honor near his birthplace in Diamond, Missouri. To this very day, the Missouri Department of Agriculture states on their website, “Dr. Carver and the peanut helped save the economy of the southern part of the U.S.” George Washington Carver’s success could be measured in many ways, but to George, only one way mattered. As George himself said, “It is not the style of clothes one wears, neither the kind of automobiles one drives, nor the amount of money one has in the bank that counts. These mean nothing. It is simple service that measures success." George’s faith inspired him to use all of his abilities, especially his scientific ones, to bring help and harmony to people. Tuskegee offers the following tribute to the way he combined faith and science: “Dr. Carver’s practical and benevolent approach to science was based on a profound religious faith to which he attributed all his accomplishments. He always believed that faith and inquiry were not only compatible paths to knowledge, but that their interaction was essential if truth in all its manifold complexity was to be approximated. “Always modest about his success, he saw himself as a vehicle through which nature, God and the natural bounty of the land could be better understood and appreciated for the good of all people. “Dr. Carver took a holistic approach to knowledge, which embraced faith and inquiry in a unified quest for truth. Carver also believed that commitment to a Larger Reality is necessary if science and technology are to serve human needs rather than the egos of the powerful. His belief in service was a direct outgrowth and expression of his wedding of inquiry and commitment.” President Franklin Roosevelt wrote about George, “All mankind are the beneficiaries of his discoveries in the field of agricultural chemistry. The things which he achieved in the face of early handicaps will for all time afford an inspiring example to youth everywhere." The words on George’s gravestone sum up his life well: “He could have added fortune to fame, but caring for neither, he found happiness and honor in being helpful to the world.” Today, let’s follow this marvelous man’s example and never give up learning more about the unique interests God has given to each of us and developing our skills to serve the people around us. Sources:

0 Comments

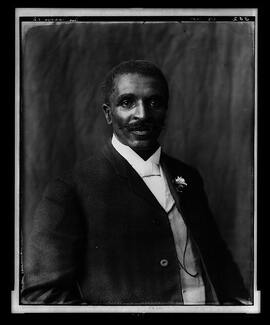

Greetings! Today I want to share the first part of a story with you about a stupendous man whose faith led him to marvelous scientific accomplishments that helped many people. Perhaps you’ve heard of him—he’s sometimes referred to as “The Peanut Man.” But long before he earned that title, he was known as “Carver’s George.” You see, George Washington Carver, the famous scientist who used chemistry and agriculture (the study of farming) to improve the lives and work of many poor Southern farmers, began life as a slave. George was born, according to his own record, “in Diamond Grove, Missouri, about the close of the great Civil War, in a little one-roomed log shanty, on the home of Mr. Moses Carver…the owner of my mother….” While he was still just a baby, men attacked the Carver farm and captured George, his mother Mary, and his sister in order to sell them in another state. All of Moses Carver’s efforts only recovered baby George. Without any parents to care for him, Moses and Susan Carver raised George themselves, even after the government legally freed all slaves in 1865. Since George’s poor health wouldn’t allow him to do much physical work, Susan taught him other skills in addition to reading and writing, like cooking, sewing, gardening, and creating home remedies from herbs. George loved learning and found plants especially fascinating. He studied the plants around him and experimented with ways to help them grow better. He became so good at it that neighboring farmers nicknamed him “the plant doctor.” But George knew there was more to learn beyond the Carver farm. Sometime around age eleven or twelve, George went to live with an African American couple named Andrew and Mariah Watkins so he could study at a one-room school for African Americans. Mariah supplemented his school studies with further training in using herbs to help heal people. George soon learned all he could there and spent the next years of his life moving from town-to-town, working a variety of jobs (including cooking, housework, laundry, and farming) as he tried different schools. He never lost his interest in nature and developed an ability to draw the plants and animals he studied. Finally, in 1880, he completed his high school education in Minneapolis, Kansas. Even after going to all that effort just to graduate high school, George was still determined to learn more. At first, Kansas’s Highland College accepted his application to enroll in their school. Then, exasperatingly and unfairly, once George arrived and college officials saw the color of his skin, they turned him away. George returned to studying and experimenting on his own. Finally, some white friends, the Milhollands, pushed George to give college another try, and in 1890, Simpson College welcomed him. George started his college career focused on the arts until one of his professors, Etta Budd, persuaded him to pursue botany at Iowa State Agricultural School. George graduated with a Bachelor of Science Degree in 1894, something no other African American had achieved before him. At his professors’ request, George continued his education and graduated with his Master of Agriculture Degree in 1896. He was well on his way to living out the words of what became his favorite poem, “Equipment,” by Edgar A. Guest: Figure it out for yourself, my lad, You've all that the greatest of men have had, Two arms, two hands, two legs, two eyes And a brain to use if you would be wise. With this equipment they all began, So start for the top and say, “I can.” Read the rest of the poem here! Next week I’ll be sharing about all the marvelous ways that George helped improve the lives of many people by using the hard-earned knowledge he had equipped himself with! Sources:

Dr. Fizzlebop walks fellow scientists through a super simple, colorful, and FIZZTASTIC experiment about fizz and hearts! Fizzlebop Lab assistants will have a fizzy fun time making these STEAM focused hearts for Valentine's Day. Give you a friend, parent, grandparent, sibling, or the one you love! These Fizzy Heart works for Art will bring happiness to someone you love!

The Lava Lamp Experiment was the second-ever appearance of Dr. Fizzlebop. This episode was created especially for Tyndale Kids' Summer Camp, which launched in 2020 as an effort to reach kids and families with hope during the beginning of the pandemic. This episode led to the creation of Faith and Science with Dr. Fizzlebop devotional and launched the Fizzlebop web series.

Dr. Fizzlebop walks fellow scientists through a wondrous experiment about plans. You'll learn how plants grow through a super simple hands-on experiment with only a few ingredients.

|

Dr. FizzlebopI believe in the four Fs: Faith, Family, Fun, and FIZZ! Faith and Science with Dr. Fizzlebop: 52 Fizztastically Fun Experiments and Devotions for FamiliesArchives

December 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed